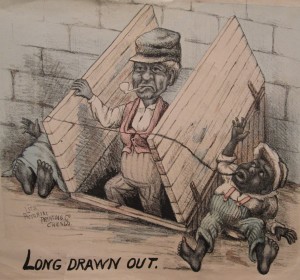

An original chalk-manner stone lithograph (with ink and watercolor) dated by me to approximately 1864 or 1865 and possibly by well-known artist Louis Kurz. I have information indicating that this company was founded in either 1864 or 1865 and closed after the Great Fire of 1871. The piece measures approximately 9 ¼ x 10 ¾ inches and has a few condition issues as pictures but easily fixed. There is also a small tear on the bottom right lower third side. Mr. Kurz was famous for his Civil War chromolithographs while partnered as part of Kurz and Allison. These images were pro Union and sympathetic to the African American cause. I would say the title “Long Drawn Out” refers to both the Civil War and the African American struggles. Rising from a basement, an apparent weary African American soldier with aged and civilian symbolism is relieving the younger generation (as shown by the tooth pull) and bringing hope. It appears the juvenile nature of the reclined man represents hope for a greater future as well. All this is just my take and I’m interested to hear any other opinions. Thanks for looking at this rare item and please read some great selections from a University of Iowa article re: Kurtz and Allison.

The Chicago Lithographing Company, established in 1864 by Louis Kurz and several partners and reorganized by Edward Carqueville and Charles Shober after the Chicago fire of 1871, printed Camille N. Drie’s view of Galveston in 1871 as well as D. D. Morse’s views of Fort Worth and McKinney. www.birdseyeviews.org Amon Carter Museum

Civil Rights in Popular Prints: Kurz and Allison’s Civil War Series Barbaranne E. Mocella Liakos, University of Iowa Montage April 2008

Kurz was born in Austria and moved to Milwaukee with his family as a youth. He later moved to Chicago, where in 1865 he co-founded the Chicago Lithographing Company. After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 Kurz returned to Milwaukee where he founded the American Oleograph Company the next year. In 1878 he again returned to Chicago where he would pass the rest of his life. He continued at the firm of Kurz and Allison until his death in 1921. As a group the prints represent black Americans as equals to their white Union counterparts, and as more able, or—as in the case of the Fort Pillow Massacres— more human than their white Confederate enemies. Pro-Union publications usually characterized Union militia, both black and white soldiers, as superior to Confederate, but multiple depictions of blacks as equally able to fight is unique in print sets of this time.24 Kurz and Allison’s predisposition towards scenes representing the strength and resolve of black soldiers over and above a need for accuracy shows how committed the firm was to advancing the larger discourse surrounding civil rights.

During the Civil War the majority of Chicago residents were pro-Union. This was not an overwhelming majority, however, and anti-Union, anti-abolitionist rhetoric was also evident. In Rally ‘Round the Flag: Chicago and the Civil War author, Theodore Karamanski, explains that, “Although southerners often denounced the city as a ‘nigger loving town’ and a den of ‘Black Republicanism,’ Chicago was not strongly abolitionist.”45 But, like other northern cities, there were various abolitionist groups and small free black communities. In a paper read before the Chicago Historical Society in 1890, Union supporter Augustus Harris Burley noted angrily, “ . . . we were surrounded by traitors in Chicago, and a large proportion of the people of Southern Illinois sympathized with the South . . . . ”46 Kurz and Allison’s images of Black soldiers, however, refuted the notions of the “traitors” and supported the calls for abolition. In the mid nineteenth century Chicago was becoming a booming metropolis. During the war years the population grew from 110,000 to 190,000.47 By the 1890’s the number was 1,100,000. Blacks made up a small percentage of this population, but their numbers continued to rise steadily due to migration from the South. Karamanski writes, “The streets thronged with newcomers drawn to the city by its reputation for commercial opportunity and its open throttle attitude towards the future.”49 This reputation was surely the draw for Louis Kurz who sought to break into the printing industry. Unlike eastern states involved in the war, the conflict actually helped to strengthen the economy of the windy city.

The two main ethnic groups in the city were Germans and the Irish. The two had been political allies for many years until 1860 when the Germans in Chicago backed Lincoln for president. The need for jobs increased the tension between the two immigrant groups. The Irish generally made up the blue collar work force at the time, while the Germans were skilled tradesmen and middleclass shopkeepers much like Kurz.50 The Irish had come to America for economic reasons, and the Germans left their home country for political ones. Karamanski explains, “For the Germans, slavery was an insult to democratic ideals, while emancipation was perceived as a potential economic threat to the less well off Irish.” Kurz was Austrian, not German, however it is probable that his loyalty lay with his fellow shopkeepers and German speakers and consequently with the abolitionists. Although blacks were the lowest in the immigrant hierarchy, newcomers of all backgrounds were often socially restricted in the same ways. Perhaps Kurz felt a kinship to blacks for this reason also. Illinois’ so called “black laws” did, however, deny Blacks basic civil rights and forced free Blacks to provide proof of their status. In an editorial in Harper’s Weekly George William Curtis compared Illinois to several slave states, “The black laws of Illinois, although Illinois is a free State, were as much a part of the code of slavery as any slave law of Arkansas or Mississippi . . . . ” The black laws were finally repealed in 1864 due to considerable public petitions circulated and signed to influence the state legislature. Through the skillful and sympathetic inclusion of imagery containing heroic black figures Kurz and Allison and their Civil War print series became active participants in the ongoing war— after The War—to give black Americans the civil rights they so rightly deserved.